RobertSchneiker.com

Between 56–34 million years ago our planet was much

warmer than today. Since the extinction of the

dinosaurs 66 million years ago, the Earth had been

warming due to increasing levels of atmospheric CO

2

.

By 56 million years ago CO

2

reached 800–1,400 ppm.

Global temperatures were over 10°C (18°F) higher

than today. Known as hothouse Earth, the warm

climate remains an enigma.

The already warm climate was punctuated by abrupt

global heat waves called hyperthermals. The largest,

the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM),

occurred 56 million years ago. Atmospheric

concentrations of CO

2

climbed to 1,600–2,000 ppm,

with some estimates as high as 3,000 ppm. Over a few thousand years global temperature increased 4–8°C (7–14.5°F). Temperate

rain forests reached the Arctic, while palm trees and alligators lived in Wyoming -- indicating that unlike today, continental

interiors were not dramatically colder during the winter than coastal regions of the same latitude.

The PETM was produced by a release of between 4,300–15,400 gigatons of CO

2

to the atmosphere. That is somewhere between

1–3 times the total estimated fossil fuel reserves on Earth today! To put that in perspective, since the start of the Industrial

Revolution, in 1751, we have released 337 gigatons of CO

2

. That amounts to only 2–8 percent of the CO

2

released during the

PETM! The evidence is scant, but it appears the release took 10,000–20,000 years. Although one estimate claims the entire

release occurred in as little as 13 years.

With that much CO

2

, in the atmosphere, the oceans became so acidic limestone deposition dramatically slowed, then stopped.

Causing the extinction of numerous marine organisms that rely on CaCO

3

to build their shells. Eventually, ocean acidity reached

the point where instead of depositing limestone it dissolves, producing a dissolution horizon. This dissolution horizon makes the

hyperthermal contact appear very abrupt. Deprived of limestone, deposition principally consists of iron rich clays. The clay had

always been there but was masked by the significantly higher rates of limestone deposition.

What causes hyperthermals and where the CO

2

came

from remains a mystery. No single source appears

capable of releasing that much CO

2

, making it likely

the release was produced by multiple sources. The

release likely involved some sort of positive

reinforcing feedback loop that sustained and amplified

the warming. Based on carbon isotope ratios, an

extraterrestrial source, including comet impacts, have

been ruled out. Instead, carbon isotope ratios point to

a release of “organic” CO

2

from some sort of fossil fuel

reserve.

Dawn of the New

You might be surprised to learn that, instead of an extinction, the PETM coincides with a sudden explosion in animal diversity. For nine million years mammals were slowly diversifying, filling the ecological niches opened by the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Then 56 million years ago, in a geologic blink of the eye, the world changed – mammals diversified to fill the land, sea, and air. This is why geologists back in 1833 called it the Eocene, which means the “Dawn of the New.” This rapid diversification is sometimes referred to as the Eocene Explosion. It marks the beginning of the modern world, with the first appearance of many mammalian orders including primates, horses, and camels.Hyperthermals

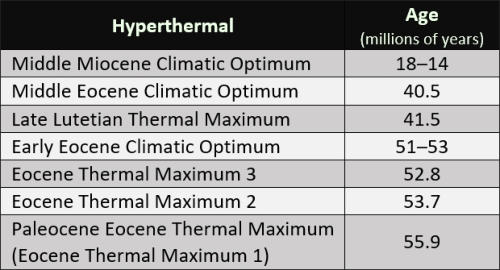

As unexpected as the PETM is, it turns out it is not alone. The PETM is only one of a series of hyperthermals, each due to the release of a huge amount of CO 2 to Earth's atmosphere. A partial list of hyperthermals is presented here, and more are being discovered all the time.Middle Eocene Climatic Optimum

Based on my research, I conclude the Sphinx contains an exposure of the Middle Eocene Climatic Optimum (MECO) hyperthermal, dated to 40 million years ago. As enigmatic hyperthermals go, the MECO stands out for two reasons. First, the CO 2 did not come from an organic source, meaning an extraterrestrial source cannot be ruled out. Second, it marks the greatest warming event over the past 47 million years of global cooling.Nummulites Gizehensis

Among the marine organisms that went extinct at the start of the MECO was Nummulites gizehensis. Nummulites are large, coin shaped single cell organisms. Some nummulites have the distinction of being the largest single cell organisms that have ever lived. Closer inspection reveals seasonal variations in shell growth, indicating that some species lived for up to 100 years. Nummulites were first described by Herodotus, a Greek historian in 500 BC. He called them nummulus, the Latin word for coin, which is what they look like. The shells of N. gizehensis are between 2.5–5 cm (1–2 inches) in diameter. Each shell contains a chambered swirl structure that looks much like a coiled snake or rope. As N. gizehensis and other organisms died they settled to the sea floor, creating a mixture of shells, bones, and mud. Over millions of years the fossils and mud were compressed to form solid limestone. At Giza, the accumulation of nummulites was so great that the shells compose much of the rock from which the Sphinx was built. Although abundant with in the Sphinx body, N. gizehensis is absent in the Sphinx neck and head. It is the extinction of N. gizehensis at the neck that marks the start of the MECO. The associated abrupt dissolution horizon forms the base of the Sphinx chin.Mehen

To the ancient Egyptians N. gizehensis was Mehen, both a snake-god and a board game. Mehen was played from 5,000–4,300 years ago, making it one of the oldest known board games. Archaeologists have discovered game boards and playing pieces, but the rules of play have never been found. It is thought that 2–4 players took turns rolling dice (throwing sticks), moving their piece to the center and back. If a piece lands on another, the other piece is bumped to the starting square. On reaching the center, the player’s piece is exchanged for a lion. It now begins its journey back to the start. If a lion lands on an occupied space the other piece is kicked off the board. The winner is the last player with a lion on the board. You can learn more about the Mehen board game here.

Hothouse Earth

Eocene: 56-34 million years ago

Mysteries of the

Great Sphinx

© Robert Adam Schneiker 2025

RobertSchneiker.com

Between 56–34 million years ago our planet was

much warmer than today. Since the extinction of the

dinosaurs 66 million years ago, the Earth had been

warming due to increasing levels of atmospheric

CO

2

. By 56 million years ago CO

2

reached 800–1,400

ppm. Global temperatures were over 10°C (18°F)

higher than today. Known as hothouse Earth, the

warm climate remains an enigma.

The already warm climate was punctuated by abrupt

global heat waves called hyperthermals. The largest,

the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM),

occurred 56 million years ago. Atmospheric

concentrations of CO

2

climbed to 1,600–2,000 ppm,

with some estimates as high as 3,000 ppm. Over a

few thousand years global temperature increased

4–8°C (7–14.5°F). Temperate rain forests reached

the Arctic, while palm trees and alligators lived in

Wyoming -- indicating that unlike today, continental

interiors were not dramatically colder during the

winter than coastal regions of the same latitude.

The PETM was produced by a release of between

4,300–15,400 gigatons of CO

2

to the atmosphere.

That is somewhere between 1–3 times the total

estimated fossil fuel reserves on Earth today! To put

that in perspective, since the start of the Industrial

Revolution, in 1751, we have released 337 gigatons

of CO

2

. That amounts to only 2–8 percent of the CO

2

released during the PETM! The evidence is scant, but

it appears the release took 10,000–20,000 years.

Although one estimate claims the entire release

occurred in as little as 13 years.

With that much CO

2

, in the atmosphere, the oceans

became so acidic limestone deposition dramatically

slowed, then stopped. Causing the extinction of

numerous marine organisms that rely on CaCO

3

to

build their shells. Eventually, ocean acidity reached

the point where instead of depositing limestone it

dissolves, producing a dissolution horizon. This

dissolution horizon makes the hyperthermal contact

appear very abrupt. Deprived of limestone,

deposition principally consists of iron rich clays. The

clay had always been there but was masked by the

significantly higher rates of limestone deposition.

What causes hyperthermals and where the CO

2

came

from remains a mystery. No single source appears

capable of releasing that much CO

2

, making it likely

the release was produced by multiple sources. The

release likely involved some sort of positive

reinforcing feedback loop that sustained and

amplified the warming. Based on carbon isotope

ratios, an extraterrestrial source, including comet

impacts, have been ruled out. Instead, carbon

isotope ratios point to a release of “organic” CO

2

from some sort of fossil fuel reserve.

Dawn of the New

You might be surprised to learn that, instead of an extinction, the PETM coincides with a sudden explosion in animal diversity. For nine million years mammals were slowly diversifying, filling the ecological niches opened by the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Then 56 million years ago, in a geologic blink of the eye, the world changed – mammals diversified to fill the land, sea, and air. This is why geologists back in 1833 called it the Eocene, which means the “Dawn of the New.” This rapid diversification is sometimes referred to as the Eocene Explosion. It marks the beginning of the modern world, with the first appearance of many mammalian orders including primates, horses, and camels.Hyperthermals

As unexpected as the PETM is, it turns out it is not alone. The PETM is only one of a series of hyperthermals, each due to the release of a huge amount of CO 2 to Earth's atmosphere. A partial list of hyperthermals is presented here, and more are being discovered all the time.Middle Eocene Climatic Optimum

Based on my research, I conclude the Sphinx contains an exposure of the Middle Eocene Climatic Optimum (MECO) hyperthermal, dated to 40 million years ago. As enigmatic hyperthermals go, the MECO stands out for two reasons. First, the CO 2 did not come from an organic source, meaning an extraterrestrial source cannot be ruled out. Second, it marks the greatest warming event over the past 47 million years of global cooling.Nummulites Gizehensis

Among the marine organisms that went extinct at the start of the MECO was Nummulites gizehensis. Nummulites are large, coin shaped single cell organisms. Some nummulites have the distinction of being the largest single cell organisms that have ever lived. Closer inspection reveals seasonal variations in shell growth, indicating that some species lived for up to 100 years. Nummulites were first described by Herodotus, a Greek historian in 500 BC. He called them nummulus, the Latin word for coin, which is what they look like. The shells of N. gizehensis are between 2.5–5 cm (1–2 inches) in diameter. Each shell contains a chambered swirl structure that looks much like a coiled snake or rope. As N. gizehensis and other organisms died they settled to the sea floor, creating a mixture of shells, bones, and mud. Over millions of years the fossils and mud were compressed to form solid limestone. At Giza, the accumulation of nummulites was so great that the shells compose much of the rock from which the Sphinx was built. Although abundant with in the Sphinx body, N. gizehensis is absent in the Sphinx neck and head. It is the extinction of N. gizehensis at the neck that marks the start of the MECO. The associated abrupt dissolution horizon forms the base of the Sphinx chin.Mehen

To the ancient Egyptians N. gizehensis was Mehen, both a snake-god and a board game. Mehen was played from 5,000–4,300 years ago, making it one of the oldest known board games. Archaeologists have discovered game boards and playing pieces, but the rules of play have never been found. It is thought that 2–4 players took turns rolling dice (throwing sticks), moving their piece to the center and back. If a piece lands on another, the other piece is bumped to the starting square. On reaching the center, the player’s piece is exchanged for a lion. It now begins its journey back to the start. If a lion lands on an occupied space the other piece is kicked off the board. The winner is the last player with a lion on the board. You can learn more about the Mehen board game here.

Hothouse Earth

Eocene: 56-34 million years ago

Mysteries of the

Great Sphinx